For most people, color is an integral part of everyday life that is often taken for granted. However, there are millions of people worldwide who experience the world differently due to color vision deficiencies, commonly known as color blindness.

Color blindness is a vision defect that prevents people from distinguishing certain colors or perceiving them differently than people with normal color vision.  While color blindness can present challenges, it does not prevent people from leading rich, productive lives with the right support and accommodations. This article aims to provide an in-depth understanding of color blindness, its causes and impacts, and how we can build a more inclusive world for the color blind community.

While color blindness can present challenges, it does not prevent people from leading rich, productive lives with the right support and accommodations. This article aims to provide an in-depth understanding of color blindness, its causes and impacts, and how we can build a more inclusive world for the color blind community.

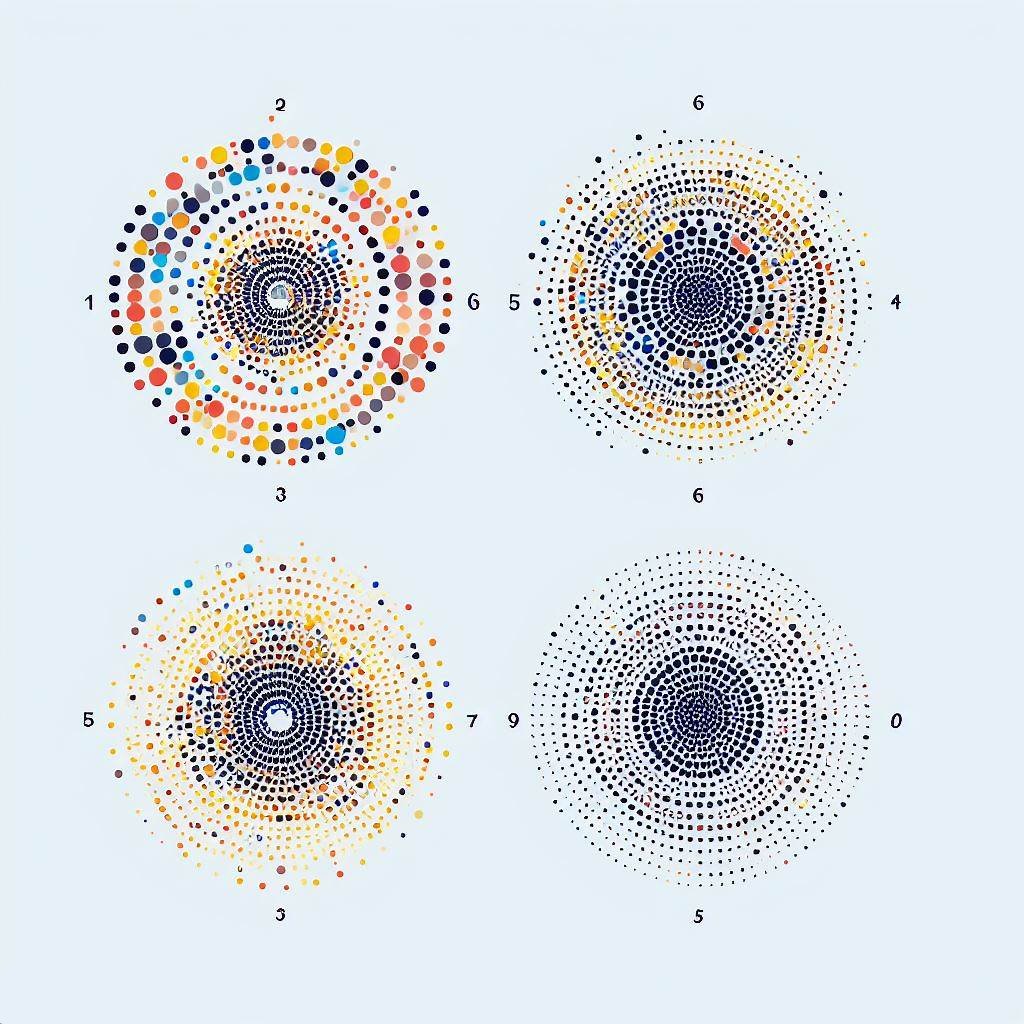

There are different types and degrees of color blindness:

Red-green color blindness is the most common form, making it difficult to distinguish between reds, greens, browns, and oranges.

Blue-yellow color blindness is less common but causes problems differentiating blues from greens and yellows from pinks.

Total/complete color blindness, or monochromacy, is very rare but results in only seeing shades of gray.

About 1 in 12 men (8%) and 1 in 200 women have some form of color vision deficiency. Red-green deficiency is inherited and sex-linked, meaning it is passed on through genes on the X chromosome and primarily affects males. Blue-yellow color blindness affects males and females equally.

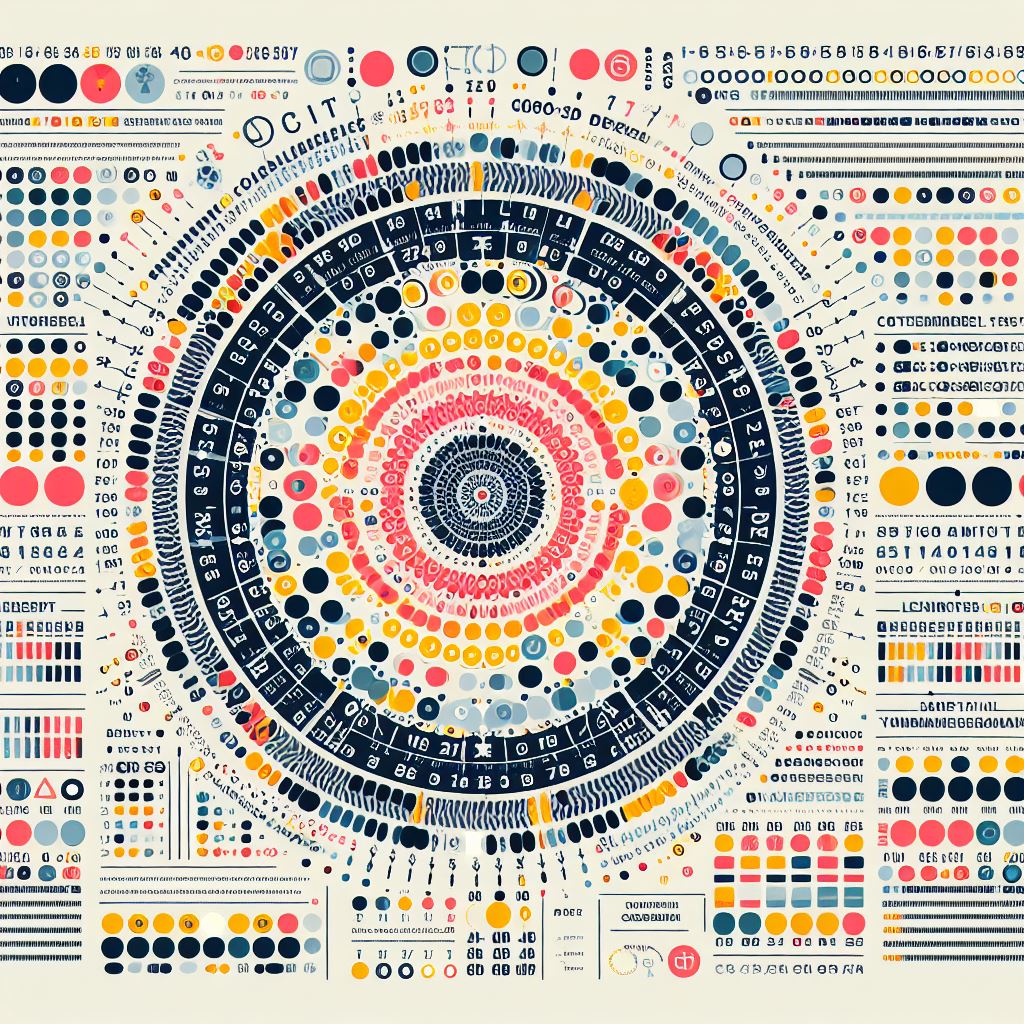

Color blindness is usually detected in childhood through screening tests. The most common diagnostics are:

Ishihara test: Identifying numbers made up of colored dots.

Anomaloscope: Matching red/green or blue/yellow light mixtures.

Genetic testing: Analyzing DNA for defects in color vision genes.

While these methods help classify color blindness, individual perceptions of color can vary widely. The degree of color blindness ranges from mild to severe based on how much overlap there is in how the eyes detect light in the red/green or blue/yellow spectrum.

In most cases, color blindness is inherited genetically and runs in families. The genes for red and green perception are located on the X chromosome. Females have two X chromosomes, so a defect in one gene can be compensated for by the other intact gene. Males only have one X chromosome, so a genetic defect results in color blindness.

The specific genetic mutations that cause color blindness involve defects in the photopigments of cone cells in the retina. These photopigments normally absorb different wavelengths of light that our brain interprets as color. With defective photopigments, the cones cannot distinguish light correctly, leading to color confusion.

Besides genetic factors, color blindness can also be acquired later in life due to:

Diseases affecting the retina like macular degeneration and diabetes.

Physical or chemical damage to the eyes.

Some medications like digoxin and phenothiazines.

Aging and loss of cone cell function.

Regardless of the cause, color blindness is usually permanent and cannot be corrected with treatments. However, people can learn to better compensate through occupational therapy and tools to enhance color perception.

Color blindness may seem like a small inconvenience, but it can have major impacts on day-to-day life, work, and mental health. Understanding these challenges is key to supporting the color blind community.

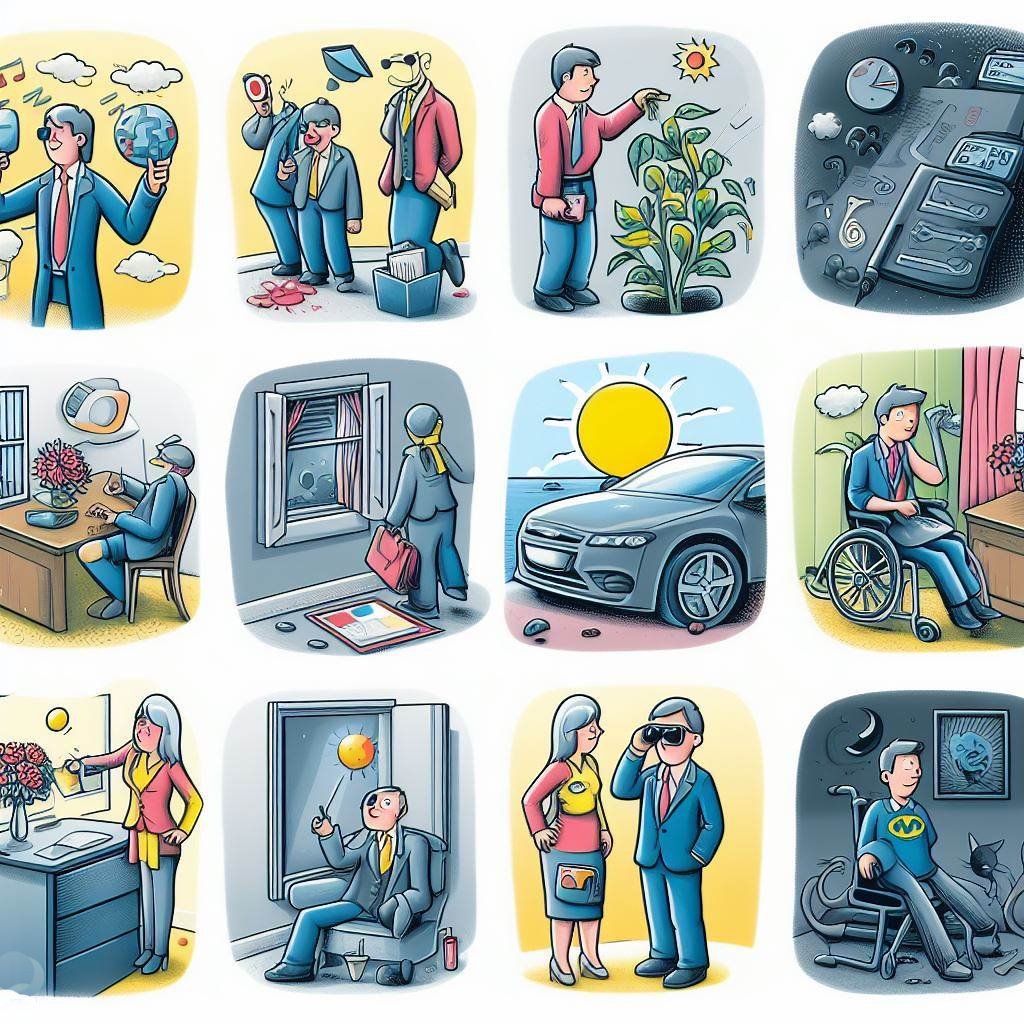

Navigating a world designed for normal color vision can be frustrating and even dangerous for the color blind. Here are some common difficulties:

Traffic lights: Red and green signals appear similar, increasing the risk of accidents. Yellow can also be hard to distinguish.

Color-coded information: Maps, charts, graphs, and warning signs using red/green/brown color codes are difficult to interpret.

Cooking: Determining if meat is cooked, fruits/vegetables are ripe, or recognizing spice colors can be problematic.

Shopping: Matching or coordinating clothes is challenging. Sales tags and prices written in colored ink are hard to read.

Electronics: Color-coded wires, buttons, and port colors are confusing. Screen displays with red/green color schemes are difficult to see.

Nature walks: Appreciating colorful flowers, plants, rocks, and autumn leaves is more limited without full color vision.

As you can see, tasks that many take for granted require careful attention and workarounds for the color blind. It takes conscious effort to navigate spaces designed for typical color vision.

Certain occupations require normal color perception for safety and effectively performing job duties. Careers that can be challenging or inaccessible for the color blind include:

Transportation: Pilots, air traffic controllers, train conductors, bus and taxi drivers.

Engineering and science: Lab work, electrical work, reading colored circuit boards, diagrams, and indicators.

Healthcare: Detecting skin discolorations, rashes, and blood samples. Mixing medications. Reading scans and test results.

Art and design: Graphic design, photography, interior design, jobs involving color mixing and matching.

Military and law enforcement: Bomb defusal, reading maps and charts, investigations, evidence analysis.

Sports: Umpires/referees making split-second calls based on color-coded uniforms and balls/pucks.

While often frustrating, these restrictions exist to uphold safety standards in fields where color discrimination is critical. But many careers can be adapted to accommodate the color blind with inclusive tools and policies.

In a world oriented around visual information, having a visual impairment can take a psychological toll. Many color blind individuals experience:

Self-consciousness: Fear of making mistakes or missing things others easily see. Feeling stressed about verifying colors.

Isolation: Feeling left out or misunderstood because they literally don't see the world the same way.

Stigma: Discrimination due to lack of awareness. Stereotyped as stupid, lazy, or careless.

Loss of confidence: Doubting abilities and reluctant to try new things or take risks.

Anxiety: Worrying about how color blindness might limit school, career, and life prospects.

Especially for children, frequent reminders that they are 'different' or 'disabled' can damage self-esteem. But when provided the proper coping strategies and accommodations, color blindness doesn't have to hold anyone back from success and happiness.

Creating an inclusive world for color blind individuals benefits everyone. Here are some ways we can show support:

Use shapes, textures, patterns, and labels rather than just colors to convey meaning.

Choose color-combinations that maximize contrast for the color blind, like blues and yellows. Avoid red/green and blue/purple combinations.

Use multiple cues like text, symbols, or audible alerts in addition to color.

Select palettes optimized for color blindness and allow user customization of color schemes.

With some forethought, designers can make visual information accessible to all.

Where color coding is unavoidable, provide alternative ways to access critical information:

Audible pedestrian crossing signals, screenreaders, braille labels.

Tactile maps, diagrams, signage.

Color identifying apps or visual aids like glasses that enhance color perception.

Swatches, photos, or physical objects for color matching/comparison.

While not perfect substitutes, these tools help fill in information gaps.

Combating stigma and isolation requires spreading awareness that color blind people have a common visual variation, not a disability or disorder. Ways to foster understanding include:

Educating children and adults about color blindness through workshops, activities, and curriculum.

Advocating for color blind individuals by acknowledging challenges and offering accommodations.

Normalizing questions like "what color is this to you?" to understand the color blind perspective.

Promoting inclusion by valuing diverse experiences and abilities.

A little compassion goes a long way in making the color blind feel supported and empowered.

Color blindness affects millions worldwide, causing difficulties most don't realize. But it does not define or limit who color blind people are. With inclusive practices, technology, and greater awareness, we can break down barriers and understand color blindness not as a disability but simply a different way of seeing. When we make the necessary adjustments to accommodate the color blind, we create a society that embraces vision diversity and enables everyone to thrive.